Archive

Amsterdam cyclists ride fastest

Does cycling-specific infrastructure slow you down? Can you ride faster on streets than on bicycle paths?

Some cyclists, many of whom seem to be of the vehicular persuasion, argue this point vociferously. John Forester may have been the first, with this pip from 2001 (among others):

The bikeway advocates are so imbued with the imagined virtues of the Dutch bikeway system, that it makes cycling safe for the incompetent and creates many cyclists where there were few before, that they have transformed, in their own minds, the defects of the Dutch system, its slow speed and long delays, into virtues.

The argument has stuck around even into this, the year of our lord 2015, the supposed year of hoverboards and powered shoelaces. That such myths and inanities persist probably has much to do with lack of experience; apparently, most cyclists in the U.S., for instance, have never ridden in a place with real bicycle infrastructure. Even John Forester, critic-in-chief of Amsterdam-style bicycle lanes, never visited the country.

Enter Strava data:

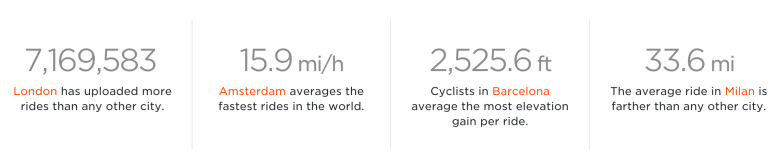

Riders in Amsterdam, that city criss-crossed by bicycle lanes and infrastructure, enjoy the fastest average speed (15.9 mph) of any major city that Strava tracks. For quick comparison, here are a few other cities:

- Los Angeles: 13.1 mph

- San Francisco: 12.9 mph

- New York City: 13.5 mph

To be sure, Strava results are easy to criticize for their reliance on data-hungry, athletic riders, those who belong to a demographic that can afford and use the devices Strava requires. (I find the service helpful for tracking times and distances of my daily commute and weekend rides.) However, comparing Strava riders city-to-city has a big advantage: Strava users look similar to each other worldwide, making comparisons easy. The point? Athletic Strava users — that category of fast, competent riders that Forester liked to describe — ride faster on Amsterdam cycling infrastructure than on any type of other (mostly non-cycling) infrastructure in major cities around the world. It’s time to retire the myth that cycling infrastructure slows you down.

Do Dutch women have more time to cycle?

In a puzzling October 3 opinion article published in The Guardian, Herbie Huff and Kelcie Ralph argue that Dutch women cycle more because they have more time than U.S. women. The authors say this extra time comes from different Dutch cultural norms and social policies — like generous paternity leave — along with better city planning that makes distances between errands shorter. They conclude that improved cycling and pedestrian mobility in U.S. cities will require deep changes to social policies, ideas with “far-reaching implications and [that] require serious value shifts.”

These are thin arguments with shaky foundations. The paper they cite looks at time use in American households only. They present no equivalent study showing how Dutch households allocate time, and no studies on whether different social policies actually give women more time to cycle. Without such studies, one could invent results out of thin air. Without research to tell us, for example, how Dutch fathers spend their paternity leave, why can we assume they actually use it to help out at home? Maybe, instead, they spend more time on non-family leisure pursuits — like playing more golf. Maybe paternity leave actually changes mothers’ lives hardly at all.

But even if we grant them their assumptions, Huff and Ralph haven’t shown why giving women more disposable time means more cycling. The implicit assumption is head-scratching, that somehow women use extra time riding bicycles instead of doing something else. How can we assume this about any person or culture? Would the opposite hold — would Dutch women ride less if they had less disposable time? Would time-rich U.S. women suddenly opt to cycle? How do we know that cycling is the go-to activity once women gain more time?

Huff and Ralph don’t tackle counterexamples like New York City, where more than half of households don’t own cars and yet somehow find the time to chauffeur their children around town, all without Dutch social policies. They also don’t address why U.S. women in child-free couples, and single women without children — both classes of women presumably with more free time than their child-rearing compatriots — are less likely to cycle than their Dutch counterparts. They discount surveys where women say straight out that they are afraid on the road, effectively belittling women and their opinions. They also don’t tackle the problem of countries with social policies similar to The Netherlands (Norway, Finland) that have low-ish cycling rates.

One of the subtle and insidious assumptions underlying this article is that cycling is primarily a hobby or non-essential activity. In the cited study, cycling comes in for a mild whipping with the unsubstantiated claim that errands are “easiest to do in a private vehicle, and hard to do on a bicycle or public transit.” That is, only those people with extra time on their hands undertake cycling, perhaps because it’s slow. This assumption came under some small scrutiny in a quick Twitter exchange I had with @JennyGoBike, a car-free mother-of-three in Seattle: “Don’t assume cycling harder til you’ve wrangled 3 tots into minivan. Challenges to both.”

The Dutch — in my experience more practical and as time-conscious as any American — have created the infrastructure that turns that assumption on its head. The Dutch don’t cycle because they have extra time; they cycle because they have no time to spare. They cycle because cycling is the fastest way to get around.

The way I see it, Huff and Ralph have worked a little too hard to find a link between Dutch social policies and cycling. It may be the case that such policies are superior to American ones in every possible way, but the essential lesson of Dutch cycling does not come from them. It comes, instead, from the city planning and infrastructure build-out that has elevated cycling to a first-class, time-saving, and normal way to get around.

Crowded

Back in the 1960s, a doctor called John Calhoun put a few rats into a cage of sorts, and let them breed as they would. The goal was simply to see what he could see. Evidently, the rats, after a few generations of rapid breeding and packed conditions, took to killing one another, even eating their young, and then, ultimately, all dying. The experiment is famous, and its conclusions have been taken by some, including Calhoun himself, as a cautionary tale for humans:

For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction.

I’d like to think that he’s wrong, that we humans are a better species than that, that our superior tool-making abilities would solve these kinds of issues, but every time I read about a bit of road rage — which usually has a too-crowded roadway somewhere at its heart — I despair a little. Mix these frequent reports with last week’s NPR article on “sidewalk rage” and the New Yorker‘s recent piece called “Crush Point,” about the fatal actions of crowds that want to do something (versus, say, having to deal with traffic), and I find myself wondering whether anything can help at all. Maybe we aren’t so different than the rats, after all.

I am a bicycle enthusiast, which means I usually ride for the sheer pleasure of the road, and not primarily to better my environment. When I look at bicycles from a public policy perspective, however, I have to think that among their benefits is a solution to crowded roadways. If I’m right, then our cities should promote bicycles in any way they can, including building out a decent network of separated infrastructure, as a growing consensus says is the only way towards large ridership. But from a handful of conversations I’ve had in recent months concerning Dutch-style infrastructure, I’d say that there’s a strong undercurrent of L.A. cyclists who don’t agree at all. They really don’t want more riders on the streets. The conversations generally conclude like this: “I don’t want to be stuck behind old people and children.” The opinion usually strikes me as elitist as the cartoon characters who go to theaters to hiss Roosevelt … but never mind. I’d probably dismiss it if I hadn’t heard it from influential cyclists, the very people who shape opinion in our city.

As it happens, this fear of old people and children has no basis in reality, at least not in Holland, where they do have lots of cyclists, and where we ought to look for examples of how to built our own network. Over there, you mostly can ride as fast as you want, faster than you could on streets packed with cars. The Dutch live in one of the most densely populated countries on earth (denser than even China or India), and have been working through these problems for years. (If California were as densely populated as the Netherlands, we would number somewhere near 160 million — people, that is, not rats.) Bicycles have long been part of their transportation solution, and when they speak of transportation issues, it’s common to hear them wonder how much more crowded their road space would be without bicycles. Nowadays, Dutch cycling infrastructure forms what the Dublin City Council cycling officer, Ciaran Fallon, called “a mass public transport system.” In effect, cycling is public transportation, and factored into the design of every street, everywhere.

I sometimes hear arguments that cycling is well and good for Holland precisely because the country is so dense, but cycling doesn’t work in places like California, which is only a fraction as populated. It’s a flimsy excuse, really, for density is one of those arguments that people seem to use to whatever political or personal purpose they have in mind. If you don’t want cycle track laid down on your streets, you can say either that we have too little space (every inch is taken up by cars) or too much space (people drive long distances). These both might be true statements, but they can’t both reasons to discard cycle-tracks. Bicycles are a solution to high density problems, period.

Then there’s this indisputable fact: Los Angeles County fits about half of the Netherlands’ population into one-quarter of the land area — in other words, our county is roughly twice as dense as Holland. If anything, our too-crowded roadways should make us desperate for high density solutions. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s all-but-laughable suggestion last year to make the 405 a double-decker freeway hardly counts. Even when we used to be a rich country, and maybe could have afforded such monstrosities, it wouldn’t have made sense. Nowadays, not at all.

But whatever the case, this elitist, “I-don’t-want-no-more-cyclists” attitude has got to go! If we expect someday to have any sort of political clout, if we expect to have our laws changed to make our roads safer, if we expect cycling to become a natural and normal part of everyday life, we need everyone on bicycles, the young and the old, the new and the wizened. We need to foster beginning riders and tolerate the inexperienced. We need to crowd our streets and our bike paths with riders of all shapes and sizes. We need to reach the point of saturation, where perhaps, someday, we have the problems that come from crowds, problems that would be nice to have by comparison to those we have now.

Burden of Proof

In translation, Article 185 of the Dutch Road Traffic Act seems to hold drivers “strictly liable” in crashes with vulnerable road users like pedestrians and cyclists. Hans Voerknecht’s layperson description of its relatively heavy consequences to drivers has created small tremors in the American bicycle-and-pedestrian blogosphere. With so many traffic incidents resulting from careless drivers, one might wonder whether strict liability might not incentivize better driving behavior, especially behavior directed towards vulnerable road users.

Article 185 does seem to come very close to the American concept of “liability without fault,” which may be the simplest definition of strict liability. While I don’t speak Dutch, what little I’ve been able to gather about the law corresponds well to Voerknecht’s basic outlines: drivers of motor vehicles on the road are strictly liable to vulnerable users outside their car (but not passengers). If drivers can show contributory negligence, their liability may be mitigated, although they will always be at least fifty percent liable, and in cases involving children under fourteen, they are always one-hundred percent liable. Drivers can escape liability only by showing force majeure; for instance, someone else was driving the car, or the injured person was trying to commit suicide. In one case I found, a moped rider escaped liability for killing a drunken man who had fallen asleep on an unlit road, at night, and could not be seen under the circumstances. By contrast, a Dutch friend of mine found himself having to pay for damages to a young cyclist even though every witness he had agreed that the crash was the boy’s fault.

I think it’s difficult to understand the role of Article 185 without at least a nod to Netherland’s tort law, its social welfare system, and its auto insurance requirements. This backdrop may create a more favorable environment for legislators to place a higher degree of responsibility on drivers, especially by comparison to our own, sometimes skewed system. For example, recoveries for injuries seem to be downright modest by comparison to some awards in the U.S. According to one paper I located, the “loss of one leg, below knee” will usually mean an award of 15,000 to 20,000 euros, far less than, say, the Los Angeles attorney who successfully sued for $4.5 million for “a switchman who lost his leg below the knee.” Similarly, Holland’s mandatory and highly regulated medical insurance coverage means that injury costs may often be covered by health insurance, with no further look towards negligent drivers. Too, my Dutch friends tell me that auto insurance in Holland is issued for cars and goes on the registration record of the car. As such, I would expect that car insurance compliance is higher than in the States, where insurance is for drivers (not cars), and only checked after a crash or in the rare instances that police pull over drivers. Each of these elements allows legislators to tilt the playing field towards vulnerable users without creating a political maelstrom.

In American jurisprudence, liability without fault has long held an uncomfortable position. Our laws and court opinions rarely extend strict liability in a civil context, and the few instances we have are riddled with seeming inconsistencies. California statute will hold you strictly liable if your dog bites the neighbors, but not when your cat rips their couch to shreds. Our courts have developed strict liability theories for product manufacturers and “abnormally dangerous activities,” but have carved out many exceptions. You may find it ironic that driving is not considered an abnormally dangerous activity, given the widespread carnage autos wreak on our roads, but it falls under a “common usage” exception. Activities aren’t abnormally dangerous if everyone is doing them.

(I think it’s not too hard to imagine a different opinion about the car’s danger if it were introduced today.)

I have few hopes of California legislators suddenly passing a Dutch-style strict liability law. While you can make a very good argument that drivers should have high levels of responsibility for their conduct, and owe a substantial duty of care towards vulnerable road users, you’d have to make those arguments in context of our broader legal, health care, and road system. Vulnerable road users often suffer more than the drivers who injure them, but our legal system generally puts liability in some relation to fault, and not merely to the gravity of injury. It’s a morally questionable position to hold people completely liable for a crash no fault of their own, especially when the financial and familial consequences can be catastrophic.

But still.

Cyclists have named whole categories of driver excuses based on their commonality: the SMIDSY (“sorry, mate, I didn’t see you”) and the SWiSS (“single witness suicide serve”) are two I know; there may be others. The near-insouciant means with which these excuses are employed sometimes stagger my faith in the basic goodness of humanity. They are the punch lines to the old joke that driving is the easiest way to get away with murder. They also point up a basic problem of determining fault in collisions with cyclists and pedestrians: vulnerable users are often rendered incapable of being effective witnesses, and the tell-tale signs that wrecked cars leave (skid marks, crash damage location) are sometimes confusing or absent altogether.

Our traffic systems, our infrastructure, our laws, and our law enforcement are all set up for cars. I don’t think any of these systems is necessarily “against” cyclists and pedestrians, but their implementation has the side-effect of disadvantaging them. When it comes to fault determination, they put vulnerable users in the extraordinary position of having to do more to show fault than drivers do. Short of a Dutch-style strict liability law, what we need is some mechanism to level that field, to shift the difficulty of showing fault away from the cyclist or pedestrian.

Here’s a simple proposal: in any crash involving a driver and vulnerable road user, the burden of proof of innocence or fault is placed on the driver; that is, drivers are presumed to be at fault unless they can show otherwise. In the SWiSS cases, for instance, drivers would have to do more than allege the cyclist darted in front of them, they’d have to prove it. The SMIDSY cases would require the same.

A “rebuttable presumption of fault” wouldn’t be perfect, but it would be a start. And maybe that’s all I can ask … for now.